Gladiator (2000 film)

| Gladiator | |

|---|---|

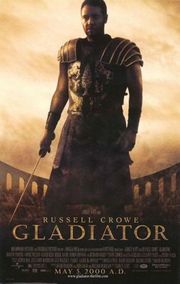

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Ridley Scott |

| Produced by | Douglas Wick David Franzoni Branko Lustig |

| Written by | David Franzoni John Logan William Nicholson |

| Starring | Russell Crowe Joaquin Phoenix Connie Nielsen Oliver Reed Derek Jacobi Djimon Hounsou Richard Harris |

| Music by | Hans Zimmer Klaus Badelt Lisa Gerrard |

| Cinematography | John Mathieson |

| Editing by | Pietro Scalia |

| Studio | Scott Free Productions Red Wagon Entertainment[1] |

| Distributed by | DreamWorks (USA) Universal Studios (non-USA) |

| Release date(s) | May 1, 2000 (Los Angeles) May 5, 2000 (United States) May 12, 2000 (United Kingdom) |

| Running time | 155 minutes Extended version: 171 minutes |

| Country | United States United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $103 million[2][3] |

| Gross revenue | $457,640,427 |

Gladiator is a 2000 historical epic directed by Ridley Scott, starring Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix, Connie Nielsen, Ralf Moeller, Oliver Reed, Djimon Hounsou, Derek Jacobi, John Shrapnel and Richard Harris. Crowe portrays the loyal General Maximus Decimus Meridius, who is betrayed when the Emperor's ambitious son, Commodus (Phoenix), murders his father and seizes the throne. Reduced to slavery, Maximus rises through the ranks of the gladiatorial arena to avenge the murder of his family and his Emperor.

Released in the United States on May 5, 2000, it was a box office success, receiving generally positive reviews, and was credited with briefly reviving the historical epic. The film was nominated for and won multiple awards; it won five Academy Awards in the 73rd Academy Awards including Best Picture. Although there have been talks of both a prequel and sequel, as of 2010, no production has begun.

Contents |

Plot

Maximus Decimus Meridius is one of the leading generals in the Roman army. He leads his men to a decisive victory against Germanic barbarians, finally ending a long war on the Roman frontier and earning the esteem of the elderly Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Marcus is dying, and though he has a son, Commodus, the emperor wishes to appoint temporary leadership to Maximus, with a desire to eventually return power to the Senate. When Commodus is told directly by his father that he will not be appointed emperor, he murders Marcus in a fit of rage and claims the throne. Maximus realizes the truth about Commodus' patricide, but he is betrayed by his friend Quintus, who instructs the guards to carry out Commodus' order to execute Maximus. Soldiers are also sent to murder Maximus' wife and son. Maximus manages to escape his assassination, and races home only to find that he was too late to save his wife and son, who have been crucified. After burying them, Maximus is found unconscious by slave traders and taken to Zucchabar, a Roman city in North Africa. There, he is bought by a slave trader named Proximo and forced to fight for his life in arena tournaments. During this time, he meets the Numidian gladiator Juba, and a barbarian from Germania named Hagen. Juba proves to be a great comfort to Maximus, and he speaks to Juba of the afterlife, encouraging him to believe that he will be reunited with his family when he dies.

In order to survive as a gladiator, Maximus appeals to the Roman people under the name and title "Spaniard". His power and fame grow until he ultimately reaches the historic Roman Colosseum and comes into contact again with Commodus. In his first event, he skilfully leads a band of other gladiators to defeat an opposing force of chariots and archers, earning the crowd's praise through his heroics in the fighting. Upon being introduced to Commodus in the arena afterward, he reveals his true identity to the stunned emperor, who considers having Maximus executed on the spot. However, the crowd votes for him to live and so Commodus backs down. Maximus later survives an indirect attack on his life when he is forced into a match against Tigris of Gaul, Rome's only undefeated gladiator. Maximus avoids being killed by tigers released into the arena and defeats Tigris. Yet Maximus ultimately refuses to obey Commodus' command to strike the death blow, and he is pronounced "Maximus the Merciful" by the crowd. This furthers Commodus' frustration, as it seems he cannot kill or humiliate Maximus without losing popular support. Following the fight, Maximus meets with his former servant Cicero, who informs him that his army is still loyal to him. Soon thereafter, Maximus forms a plot with Lucilla, Commodus' sister, and the senator Gracchus, to rejoin with his army and topple Commodus by force. Commodus, however, suspects his sister of betrayal and by indirectly threatening her young son manipulates her into revealing the plot. During Maximus' attempted escape, Commodus' guards attack Proximo's gladiator school. Hagen and Proximo are killed in the attack, while Juba and the survivors are imprisoned. Maximus makes it to the city walls, but Cicero, who was waiting for him with horses, is killed by archers and Maximus is arrested by the guards.

Now desperate to have Maximus killed, Commodus arranges a duel with him in the arena. Commodus acknowledges Maxiums as a superior fighter, and then stabs a restrained Maximus in his side with a stiletto before they enter the arena. In the midst of the fight, Maximus forces Commodus' sword from his hands. When Commodus demands a sword from the surrounding guards, Quintus orders them to sheathe their weapons. Commodus produces the hidden stiletto, but despite his handicap, Maximus defeats Commodus in driving the stiletto into Commodus' neck. With his dying words Maximus carries out Marcus Aurelius's commands, calling for Gracchus to be reinstated, the slaves to be freed, and power in Rome to be transferred to the Senate. Maximus dies in Lucilla's arms and his soul wanders into the afterlife with his family. Lucilla reiterates Maximus' wishes, reminding everyone that Maximus was a soldier of Rome and that his memory should be honored. Some time later, Juba, now free, buries Maximus' two small figurines of a woman and a boy in the ground where Maximus died.

Cast

- Russell Crowe as Maximus Decimus Meridius: a morally upstanding Hispano-Roman general in Germania, turned slave who seeks revenge against Commodus. He had been under the favor of Marcus Aurelius, and the love and admiration of Lucilla prior to the events of the film. His home is near Trujillo (in today's Cáceres, Spain). After the murder of his family he vows vengeance. Maximus is a fictional character partly inspired by Marcus Nonius Macrinus, Narcissus, Spartacus, Cincinnatus, and Maximus of Hispania.

- Joaquin Phoenix as Commodus: a vain, power hungry and sociopathic young man who is jealous of and despises Maximus because his father Marcus Aurelius favors the General over him. Commodus murders his father and desires his own sister, Lucilla. He becomes the emperor of Rome upon his father's death. He is killed by Maximus in the final battle.

- Connie Nielsen as Lucilla: Maximus' former lover and the older child of Marcus Aurelius, Lucilla has been recently widowed. She tries to resist the incestuous lust of her brother while protecting her son, Lucius.

- Djimon Hounsou as Juba: a Numidian tribesman who was taken from his home and family by slave traders. He becomes Maximus's closest ally during their shared hardships.

- Oliver Reed as Antonius Proximo: an old and gruff gladiator trainer who buys Maximus in North Africa. A former gladiator himself, he was freed by Marcus Aurelius, and gives Maximus his own armor and eventually a chance at freedom. This was Reed's final film; he died during production.

- Derek Jacobi as Senator Gracchus: one of the senators who opposed Commodus's leadership, who eventually agrees to aid Maximus in his overthrow of the Emperor.

- Ralf Moeller as Hagen: a Germanic Warrior and Proximo's chief gladiator who later befriends Maximus and Juba during their battles in Rome.

- Spencer Treat Clark as Lucius Verus: the young son of Lucilla. He admires Maximus and incurs the wrath of his uncle, Commodus, by impersonating the gladiator. Lucius is a free-spirit and likes his uncle at first until Commodus's true sinister nature comes to the fore. He is named after Lucius Verus, his alleged father and co-ruler of Marcus Aurelius.

- Richard Harris as Marcus Aurelius: an emperor of Rome who appoints Maximus, whom he dotes on as a son, to return Rome to a republican form of government but is murdered by his own son Commodus before his wish is fulfilled.

- Tommy Flanagan as Cicero: a Roman soldier and Maximus's loyal servant who provides him with information while Maximus is enslaved.

- Tomas Arana as General Quintus: another Roman general and former friend to Maximus. Made commander of the Praetorian guards by Commodus, earning his loyalty until Commodus orders the execution of his men.

- John Shrapnel as Gaius: another senator who is in close correspondence to Gracchus.

- David Schofield as Senator Falco: a Patrician, a senator opposed to Gracchus. Helps Commodus consolidate his power.

- Sven-Ole Thorsen as Tigris of Gaul: an undefeated gladiator who is called out of retirement to duel Maximus.

- David Hemmings as Cassius: runs the gladiatorial games in the Colosseum and is the arena announcer.

- Giannina Facio, Maximus's wife.

- Giorgio Cantarini, Maximus's son.

Production

Screenplay

Gladiator was based on an original pitch by David Franzoni, who went on to write all of the early drafts.[4] Franzoni was given a three-picture deal with DreamWorks as writer and co-producer on the strength of his previous work, Steven Spielberg's Amistad, which helped establish the reputation of DreamWorks. Franzoni was not a classical scholar but had been inspired by Daniel P. Mannix’s 1958 novel Those About to Die and decided to choose Commodus as his historical focus after reading the Augustan History. In Franzoni's first draft, dated April 4, 1998, he named his protagonist Narcissus, after the praenomen of the wrestler who strangled Emperor Commodus to death, whose name is not contained in the biography of Commodus by Aelius Lampridius in the Augustan History. The name Narcissus is only provided by Herodian and Cassius Dio, so a variety of ancient sources were used in developing the first draft.[5]

Ridley Scott was approached by producers Walter F. Parkes and Douglas Wick. They showed him a copy of Jean-Léon Gérôme's 1872 painting entitled Pollice Verso ("Thumbs Down").[6] Scott was enticed by filming the world of Ancient Rome. However, Scott felt Franzoni's dialogue was too "on the nose" and hired John Logan to rewrite the script to his liking. Logan rewrote much of the first act, and made the decision to kill off Maximus's family to increase the character's motivation.[7]

With two weeks to go before filming, the actors complained of problems with the script. William Nicholson was brought to Shepperton Studios to make Maximus a more sensitive character, reworking his friendship with Juba and developed the afterlife thread in the film, saying "he did not want to see a film about a man who wanted to kill somebody."[7] David Franzoni was later brought back to revise the rewrites of Logan and Nicholson, and in the process gained a producer's credit. When Nicholson was brought in, he started going back to Franzoni's original scripts and reading certain scenes. Franzoni helped creatively manage the rewrites and in the role of producer he defended his original script, and argued to stay true to the original vision.[8] Franzoni later shared the Academy Award for Best Picture with producers Douglas Wick and Branko Lustig.[4]

The screenplay faced the brunt of many rewrites and revisions due to Russell Crowe's script suggestions. Crowe questioned every aspect of the evolving script and strode off the set when he did not get answers. According to a DreamWorks executive, "(Russell Crowe) tried to rewrite the entire script on the spot. You know the big line in the trailer, 'In this life or the next, I will have my vengeance'? At first he absolutely refused to say it."[9] Nicholson, the third and final screenwriter, says Crowe told him, "Your lines are garbage but I'm the greatest actor in the world, and I can make even garbage sound good." Nicholson goes on to say that "...probably my lines were garbage, so he was just talking straight."[10]

Pre-production

In preparation for filming, Scott spent several months developing storyboards to develop the framework of the plot.[11] Over six weeks, production members scouted various locations within the extent of the Roman Empire before its collapse, including Italy, France, North Africa, and England.[12] All of the film's props, sets, and costumes were manufactured by crew members due to high costs and unavailability of the items.[13]

Filming

The film was shot in three main locations between January and May 1999. The opening battle scenes in the forests of Germania were shot in three weeks in the Bourne Woods, near Farnham, Surrey in England.[14] When Scott learned that the Forestry Commission planned to remove the forest, he convinced them to allow the battle scene to be shot there and burn it down.[15] Scott and cinematographer John Mathieson utilized multiple cameras filming at various frame rates, similar to techniques used for the battle sequences of Saving Private Ryan (1998).[16] Subsequently, the scenes of slavery, desert travel, and gladiatorial training school were shot in Ouarzazate, Morocco just south of the Atlas Mountains over a further three weeks.[17] To construct the arena where Maximus has his first fights, the crew used basic materials and local building techniques to manufacture the 30,000-mud brick arena.[18] Finally, the scenes of Ancient Rome were shot over a period of nineteen weeks in Fort Ricasoli, Malta.[19][20]

In Malta, a replica of about one-third of Rome's Colosseum was built, to a height of 52 feet (15.8 meters), mostly from plaster and plywood (the other two-thirds and remaining height were added digitally).[21] The replica took several months to build and cost an estimated $1 million.[22] The reverse side of the complex supplied a rich assortment of Ancient Roman street furniture, colonnades, gates, statuary, and marketplaces for other filming requirements. The complex was serviced by tented "costume villages" that had changing rooms, storage, armorers, and other facilities.[19] The rest of the Colosseum was created in CGI using set-design blueprints, textures referenced from live action, and rendered in three layers to provide lighting flexibility for compositing in Flame and Inferno.[23]

Post-production

British post-production company The Mill was responsible for much of the CGI effects that were added after filming. The company was responsible for such tricks as compositing real tigers filmed on bluescreen into the fight sequences, and adding smoke trails and extending the flight paths of the opening scene's salvo of flaming arrows to get around regulations on how far they could be shot during filming. They also used 2,000 live actors to create a CG crowd of 35,000 virtual actors that had to look believable and react to fight scenes.[24] The Mill accomplished this feat by shooting live actors at different angles giving various performances, and then mapping them onto cards, with motion-capture tools used to track their movements for 3D compositing.[23] The Mill ended up creating over 90 visual effects shots, comprising approximately nine minutes of the film's running time.[25]

An unexpected post-production job was caused by the death of Oliver Reed of a heart attack during the filming in Malta, before all his scenes had been shot. The Mill created a digital body double for the remaining scenes involving his character Proximo[23] by photographing a live action body-double in the shadows and by mapping a 3D CGI mask of Reed's face to the remaining scenes during production at an estimated cost of $3.2 million for two minutes of additional footage.[26][27] Visual effects supervisor John Nelson reflected on the decision to include the additional footage: "What we did was small compared to our other tasks on the film. What Oliver did was much greater. He gave an inspiring, moving performance. All we did was help him finish it."[26] The film is dedicated to Reed's memory.[28]

Historical accuracy

The film is only loosely based on historical events. Although the filmmakers consulted an academic expert with knowledge of the period of the Ancient Roman empire, historical discrepancies were incorporated by the screenwriters.[29] At least one historical advisor resigned due to the changes made, and another asked not to be mentioned in the credits. Historian Allen Ward of the University of Connecticut believed that historical accuracy would not have made Gladiator less interesting or exciting and stated: "creative artists need to be granted some poetic license, but that should not be a permit for the wholesale disregard of facts in historical fiction".[30]

Marcus Aurelius actually died of plague at Vindobona and was not murdered by his son Commodus. The character of Maximus is fictional, although in some respects he resembles the historical figures of Narcissus (the character's name in the first draft of the screenplay and the real killer of Commodus),[31] Spartacus (who led a significant slave revolt), Cincinnatus (a farmer who became dictator, saved Rome from invasion, then resigned his 6-month appointment after fifteen days),[32][33][34] and Marcus Nonius Macrinus (a trusted general, Consul of AD 154, and friend of Marcus Aurelius).[35][36] Although Commodus engaged in show combat in the Colosseum, he was strangled by the wrestler Narcissus in his bath, not killed in the arena.

Influences

The film's plot was influenced by two 1960s Hollywood films of the 'sword and sandal' genre, The Fall of the Roman Empire and Spartacus.[37] The Fall of the Roman Empire tells the story of Livius, who, like Maximus in Gladiator, is Marcus Aurelius's intended successor. Livius is in love with Lucilla and seeks to marry her while Maximus, who is happily married, was formerly in love with her. Both films portray the death of Marcus Aurelius as an assassination. In Fall of the Roman Empire a group of conspirators independent of Commodus, hoping to profit from Commodus's accession, arrange for Marcus Aurelius to be poisoned; in Gladiator Commodus himself murders his father by smothering him. In the course of Fall of the Roman Empire Commodus unsuccessfully seeks to win Livius over to his vision of empire in contrast to that of his father, but continues to employ him notwithstanding; in Gladiator when Commodus fails to secure Maximus's allegiance, he executes Maximus's wife and son and tries unsuccessfully to execute him. Livius in Fall of the Roman Empire and Maximus in Gladiator kill Commodus in single combat: Livius to save Lucilla and Maximus to avenge Marcus Aurelius, and both do it for the greater good of Rome.

Scott attributed Spartacus and Ben-Hur as influences on the film, "These movies were part of my cinema-going youth. But at the dawn of the new millennium, I though this might be the ideal time to revisit what may have been the most important period of the last two thousand years—if not all recorded history—the apex and beginning of the decline of the greatest military and political power the world has ever known."[38]

Spartacus provides the film's gladiatorial motif, as well as the character of Senator Gracchus, a fictitious senator (bearing the name of a pair of revolutionary Tribunes from the 2nd century BC) who in both films is an elder statesman of ancient Rome attempting to preserve the ancient rights of the Roman senate in the face of an ambitious autocrat — Marcus Licinius Crassus in Spartacus and Commodus in Gladiator. Both actors who played Gracchus (in Spartacus and Gladiator), played Claudius in previous films — Charles Laughton of Spartacus played Claudius in the 1937 film I, Claudius and Sir Derek Jacobi of Gladiator, played Claudius in the 1975 BBC adaptation. Both films also share a specific set piece, where a gladiator (Maximus here, Woody Strode's Draba in Spartacus) throws his weapon into a spectator box at the end of a match as well as at least one line of dialogue: "Rome is the mob", said here by Gracchus and by Julius Caesar (John Gavin) in Spartacus.

The film's depiction of Commodus's entry into Rome borrows imagery from Leni Riefenstahl's Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1934), although Ridley Scott has pointed out that the iconography of Nazi rallies was of course inspired by the Roman Empire. Gladiator reflects back on the film by duplicating similar events that occurred in Adolf Hitler's procession. The Nazi film opens with an aerial view of Hitler arriving in a plane, while Scott shows an aerial view of Rome, quickly followed by a shot of the large crowd of people watching Commodus pass them in a procession with his chariot.[39] The first thing to appear in Triumph of the Will is a Nazi eagle, which is alluded to when a statue of an eagle sits atop one of the arches (and then shortly followed by several more decorative eagles throughout the rest of the scene) leading up to the procession of Commodus. At one point in the Nazi film, a little girl gives flowers to Hitler, while Commodus is met with several girls that all give him bundles of flowers.[40]

Music

The Oscar-nominated score was composed by Hans Zimmer and Lisa Gerrard, and conducted by Gavin Greenaway. Lisa Gerrard's vocals are similar to her own work on The Insider score.[41] The music for many of the battle scenes has been noted as similar to Gustav Holst's "Mars: The Bringer of War", and in June 2006, the Holst Foundation sued Hans Zimmer for allegedly copying the late Gustav Holst's work.[42][43] Another close musical resemblance occurs in the scene of Commodus's triumphal entry into Rome, accompanied by music clearly evocative of two sections—the Prelude to Das Rheingold and Siegfried's Funeral March from Götterdämmerung—from Wagner's Ring of the Nibelungs. The "German" war chant in the opening scene was borrowed from the 1964 film Zulu, one of Ridley Scott's favorite movies. On February 27, 2001, nearly a year after the first soundtrack's release, Decca produced Gladiator: More Music From the Motion Picture. Then, on September 5, 2005, Decca produced Gladiator: Special Anniversary Edition, a two-CD pack containing both the above mentioned releases. Some of the music from the film was featured in the NFL playoffs in January 2003 before commercial breaks and before and after half-time.[44] In 2003, Luciano Pavarotti released a recording of himself singing a song from the film and said he regretted turning down an offer to perform on the soundtrack.[45] The Soundtrack is one of the best selling film scores of all time, and also amongst the most popular.

Reception

Gladiator received positive reviews, with 77% of the critics polled by Rotten Tomatoes giving it favorable reviews.[46] At the website Metacritic, which utilizes a normalized rating system, the film earned a favorable rating of 64/100 based on 37 reviews by mainstream critics.[47] The Battle of Germania was cited by CNN.com as one of their "favorite on-screen battle scenes",[48] while Entertainment Weekly named Maximus as their sixth favorite action hero, because of "Crowe's steely, soulful performance",[49] and named it as their third favorite revenge film.[50] In 2002, a Channel 4 (UK TV) poll named it as the sixth greatest film of all time.[51] Entertainment Weekly put it on its end-of-the-decade, "best-of" list, saying, "Were you not entertained?"[52]

It was not without its deriders, with Roger Ebert in particular harshly criticizing the look of the film as "muddy, fuzzy, and indistinct." He also derided the writing claiming it "employs depression as a substitute for personality, and believes that if characters are bitter and morose enough, we won't notice how dull they are."[53]

The film earned $US34.82 million on its opening weekend at 2,938 U.S. theaters.[54] Within two weeks, the film's box office gross surpassed its $US103,000,000 budget.[2] The film continued on to become one of the highest earning films of 2000 and made a worldwide box office gross of $US457,640,427, with over $US187 million in American theaters and more than the equivalent of $US269 million in non-US markets.[55]

Accolades

Gladiator was nominated in 36 individual ceremonies, including the 73rd Academy Awards, the BAFTA Awards, and the Golden Globe Awards. Of 119 award nominations, the film won 48 prizes.[56]

The film won five Academy Awards and was nominated for an additional seven, including Best Supporting Actor for Joaquin Phoenix and Best Director for Ridley Scott. There was controversy over the film's nomination for Best Original Music Score. The award was officially nominated only to Hans Zimmer, and not to Lisa Gerrard due to Academy rules. However, the pair did win the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score as co-composers.

- 73rd Academy Awards

- Best Picture

- Best Actor (Russell Crowe)

- Best Visual Effects

- Best Costume Design

- Best Sound

- BAFTA Awards

- Best Cinematography

- Best Editing

- Best Film

- Best Production Design

- 58th Golden Globe Awards

- Best Motion Picture — Drama

- Best Original Score — Motion Picture

Impact

The film's mainstream success is responsible for an increased interest in Roman and classical history in the United States. According to The New York Times, this has been dubbed the "Gladiator Effect".

It's called the 'Gladiator' effect by writers and publishers. The snob in us likes to believe that it is always books that spin off movies. Yet in this case, it's the movies — most recently Gladiator two years ago —; that have created the interest in the ancients. And not for more Roman screen colossals, but for writing that is serious or fun or both."[57]

Sales of the Cicero biography 'Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome's Greatest Politician and Gregory Hays' translation of Marcus Aurelius' Meditations received large spikes in sales after the release of the film.[57] The film also began a revival of the historical epic genre with films such as Troy, Alexander, King Arthur, Kingdom of Heaven, and 300.[58]

Home media release

The film was first released on DVD on November 20, 2000, and has since been released in several different extended and special edition versions. Special features for the Blu-ray Disc and DVDs include deleted scenes, trailers, documentaries, commentaries, storyboards, image galleries, easter eggs, and cast auditions. The film was released on Blu-ray in September 2009, in a 2-disc edition containing both the theatrical and extended cuts of the film, as part of Paramount's "Sapphire Series" (Paramount bought the DreamWorks library in 2006).[59] Initial reviews of the Blu-ray Disc release criticized poor image quality, leading to many calling for it to be remastered, as Sony did with The Fifth Element in 2007.[60]

The DVD editions that have been released since the original two-disc version, include a film only single-disc edition as well as a three-disc "extended edition" DVD which was released in August 2005. The extended edition DVD features approximately fifteen minutes of additional scenes, most of which appear in the previous release as deleted scenes. The original cut, which Scott still calls his director's cut, is also selectable via seamless branching (which is not included on the UK edition). The DVD is also notable for having a new commentary track featuring director Scott and star Crowe. The film spans the first disc, while the second disc contains a comprehensive three-hour documentary into the making of the film by DVD producer Charles de Lauzirika, and the third disc contains supplements. Discs one and two of the three-disc extended edition were also repackaged and sold as a two-disc "special edition" in the EU in 2005.

Prequel

In June 2001, Douglas Wick said a Gladiator prequel was in development.[61] The following year, Wick, Walter Parkes, David Franzoni, and John Logan switched direction to a sequel set fifteen years later;[62] the Praetorian Guards rule Rome and an older Lucius is trying to learn who his real father was. However, Russell Crowe was interested in resurrecting Maximus, and further researched Roman beliefs about the afterlife to accomplish this.[63] Ridley Scott expressed interest, although he admitted the project would have to be retitled as it had little to do with gladiators.[64] An easter egg contained on disc 2 of the extended edition / special edition DVD releases includes a discussion of possible scenarios for a follow-up. This includes a suggestion by Walter F. Parkes that, in order to enable Russell Crowe to return to play Maximus, who dies at the end of the original movie, a sequel could involve a "multi-generational drama about Maximus and the Aureleans and this chapter of Rome", similar in concept to The Godfather Part II.

In 2006, Scott stated he and Crowe approached Nick Cave to rewrite the film, but they had conflicted with DreamWorks's idea of a Lucius spin-off, who Scott revealed would turn out to be Maximus' son with Lucilla. He noted this tale of corruption in Rome was too complex, whereas Gladiator worked due to its simple drive.[65] In 2009, details of Cave's ultimately rejected script surfaced on the internet, suggesting that Maximus would be reincarnated by the Roman gods and returned to Rome to defend Christians against persecution; he would then be transported to other important periods in history, including World War II, finally playing a role in the modern-day Pentagon.[66][67]

Notes

- ↑ "Company Information". movies.nytimes.com. http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/184587/Gladiator/credits. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sale, Martha Lair; Paula Diane Parker (2005) (PDF), Losing Like Forrest Gump: Winners and Losers in the Film Industry, http://www.sbaer.uca.edu/research/allied/2005vegas/acctg%20&%20fina%20studies/30.pdf, retrieved 2007-02-19

- ↑ Schwartz, Richard (2002), The Films of Ridley Scott, Westport, CT: Praeger, p. 141, ISBN 0275969762

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Stax (April 4, 2002), The Stax Report's Five Scribes Edition, IGN, http://movies.ign.com/articles/356/356712p1.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Jon Solomon (April 1, 2004), "Gladiator from Screenplay to Screen", in Martin M. Winkler, Gladiator: Film and History, Blackwell Publishing, p. 3

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 22

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Tales of the Scribes: Story Development. [DVD]. Universal. 2005.

- ↑ John Soriano (2001) (PDF), WGA.ORG's Exclusive Interview with David Franzoni, archived from the original on 2007-12-03, http://web.archive.org/web/20071203172028/http://www.sois.uwm.edu/xie/dl/Movie+Project+Team+Folder/Movie+Project+Team+Folder/Writers/David+Frazoni-+Gladiator.pdf, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Corliss, Richard; Jeffrey Ressner (May 8, 2000), The Empire Strikes Back, Time, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,996847-2,00.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Bill Nicholson’s Speech at the launch of the International Screenwriters' Festival, January 30, 2006, http://www.screenwritersfestival.com/news.php?id=3, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 34

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 61

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 66

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 62

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 68

- ↑ Bankston, Douglas (May 2000), "Death or Glory", American Cinematographer (American Society of Cinematographers), http://www.ascmag.com/magazine/may00/pg1.htm

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 63

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 73

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Gory glory in the Colosseum, KODAK: In Camera, July 2000, archived from the original on 2005-02-09, http://web.archive.org/web/20050209185727/http://www.kodak.com/US/en/motion/newsletters/inCamera/july2000/gladiator.shtml, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Malta Film Commission - Backlots, Malta Film Commission, http://mfc.com.mt/page.asp?p=14388&l=1, retrieved 28 August 2009

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 89

- ↑ Winkler, p.130

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Bath, Matthew (October 25, 2004), The Mill, Digit Magazine, http://www.digitmag.co.uk/features/index.cfm?featureID=1152&page=1&pagepos=3, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Landau, Diana; Walter Parkes, John Logan, & Ridley Scott (2000), Gladiator: The Making of the Ridley Scott Epic, Newmarket Press, p. 89, ISBN 1557044287

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 122

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Landau 2000, p. 123

- ↑ Oliver Reed Resurrected On Screen, Internet Movie Database, April 12, 2000, http://www.imdb.com/news/wenn/2000-04-12#celeb4, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Schwartz, p.142

- ↑ Winkler, Martin (2004), Gladiator Film and History, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, p. 6, ISBN 1405110422

- ↑ The Movie "Gladiator" In Historical Perspective

- ↑ Gladiator: The Real Story, http://www.exovedate.com/the_real_gladiator_one.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Livy. Cincinnatus Leaves His Plow. Taken from The Western World ISBN 100536993734

- ↑ Andrew Rawnsley (June 23, 2002), He wants to go on and on; they all do, London: Guardian Unlimited, http://observer.guardian.co.uk/comment/story/0,,742256,00.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Llewellyn H. Rockwell Jr. (April 29, 2001), Bush, the 'Gladiator' president?, WorldNetDaily, http://www.worldnetdaily.com/news/article.asp?ARTICLE_ID=22223, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Peter Popham (October 16, 2008), Found: Tomb of the general who inspired 'Gladiator', London: The Independent, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/found-tomb-of-the-general-who-inspired-gladiator-963797.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ 'Gladiator' Tomb is Found in Rome, BBC News, October 17, 2008, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7675633.stm, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Martin M. Winkler (June 23, 2002), Scholia Reviews ns 14 (2005) 11., http://www.classics.und.ac.za/reviews/05-11win.htm, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Landau 2000, p. 28

- ↑ Winkler, p.114

- ↑ Winkler, p.115

- ↑ Zimmer and Gladiator, Reel.com, http://www.reel.com/reel.asp?node=movienews/confidential&pageid=16882, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Priscilla Rodriguez (June 12, 2006), "Gladiator" Composer Accused of Copyright Infringement, KNX 1070 NEWSRADIO, http://www.knx1070.com/pages/45400.php, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Michael Beek (June 2006), Gladiator Vs Mars - Zimmer is sued:, Music from the Movies, archived from the original on 2008-06-18, http://web.archive.org/web/20080618112502/http://www.musicfromthemovies.com/article.asp?ID=695, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Winkler, p.141

- ↑ Anastasia Tsioulcas (October 26, 2003), For Pavarotti, Time To Go 'Pop', Yahoo! Music, http://music.yahoo.com/read/news/12179048, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Gladiator, Rotten Tomatoes, http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/gladiator/, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Gladiator, Metacritic, http://www.metacritic.com/film/titles/gladiator, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ The best — and worst — movie battle scenes, CNN, April 2, 2007, http://www.cnn.com/2007/SHOWBIZ/Movies/03/29/movie.battles/index.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Marc Bernadin (October 23, 2007), 25 Awesome Action Heroes, Entertainment Weekly, http://www.ew.com/ew/gallery/0,,20041669_20041686_20153598_19,00.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Gary Susman (December 12, 2007), 20 Best Revenge Movies, Entertainment Weekly, http://www.ew.com/ew/gallery/0,,20165601_18,00.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ 100 Greatest Films, Channel 4, archived from the original on 2008-04-15, http://web.archive.org/web/20080415004921/http://www.channel4.com/film/newsfeatures/microsites/G/greatest/results/control.jsp?resultspage=01, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Geier, Thom; Jensen, Jeff; Jordan, Tina; Lyons, Margaret; Markovitz, Adam; Nashawaty, Chris; Pastorek, Whitney; Rice, Lynette; Rottenberg, Josh; Schwartz, Missy; Slezak, Michael; Snierson, Dan; Stack, Tim; Stroup, Kate; Tucker, Ken; Vary, Adam B.; Vozick-Levinson, Simon; Ward, Kate (December 11, 2009), "THE 100 Greatest MOVIES, TV SHOWS, ALBUMS, BOOKS, CHARACTERS, SCENES, EPISODES, SONGS, DRESSES, MUSIC VIDEOS, AND TRENDS THAT ENTERTAINED US OVER THE PAST 10 YEARS". Entertainment Weekly. (1079/1080):74-84

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (May 5, 2000), Gladiator Review, Chicago Sun-Times, http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20000505/REVIEWS/5050301/1023, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Schwartz, p.141

- ↑ Gladiator total gross, Box Office Mojo, http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=gladiator.htm, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Gladiator awards tally, Internet Movie Database, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0172495/awards, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Martin, Arnold (July 11, 2002), Making Books; Book Parties With Togas, The New York Times, archived from the original on January 17, 2008, http://web.archive.org/web/20080117055645/http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=990CE2D61530F932A25754C0A9649C8B63, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ The 15 Most Influential Films of Our Lifetime, Empire, June 2004, p. 115

- ↑ Gladiator, Blu-ray.com, http://www.blu-ray.com/movies/movies.php?id=4735, retrieved 2009-05-16

- ↑ Initial "Gladiator" Blu-ray Reviews Report Picture Quality Issues, Netflix, http://www.bigscreen.com/journal.php?id=1632, retrieved 2009-09-11

- ↑ Stax (June 16, 2001), "IGN FilmForce Exclusive: David Franzoni in Negotiations for Another Gladiator!", IGN, http://uk.movies.ign.com/articles/300/300625p1.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Brian Linder (September 24, 2002), "A Hero Will Rise... Again", IGN, http://uk.movies.ign.com/articles/372/372042p1.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Stax (December 17, 2002), "A Hero Will Rise - From the Dead!", IGN, http://uk.movies.ign.com/articles/380/380501p1.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Stax (September 11, 2003), "Ridley Talks Gladiator 2", IGN, http://uk.movies.ign.com/articles/437/437722p1.html, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Reg Seeton, "Ridley Scott Interview, Page 2", UGO Networks, http://www.ugo.com/channels/dvd/features/tristanandisolde/interview.asp, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ↑ Michaels, Sean (May 6, 2009). "Nick Cave's rejected Gladiator 2 script uncovered!". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2009/may/06/nick-cave-rejected-gladiator-script. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ↑ Cave, Nick, Gladiator 2 Draft, http://www.mypdfscripts.com/unproduced/gladiator-2-by-nick-cave, retrieved 16 May 2010

References

- Landau, Diana; Walter Parkes, John Logan, and Ridley Scott (2000), Gladiator: The Making of the Ridley Scott Epic, Newmarket Press, ISBN 1-5570-4428-7

Further reading

- Reynolds, Mike (July 2000), "Ridley Scott: From Blade Runner to Blade Stunner", DGA Monthly Magazine (Directors Guild of America), http://www.dga.org/news/v25_2/feat_gladiator.php3, retrieved 2007-01-31

- Schwartz, Richard (2001). The Films of Ridley Scott. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96976-2

- Stephens, William (2001), "The Rebirth of Stoicism?", Creighton Magazine, http://puffin.creighton.edu/PHIL/Stephens/rebirth_of_stoicism.htm, retrieved 2010-01-04

- Ward, Allen (2001), "The Movie "Gladiator" in Historical Perspective", Classics Technology Center (AbleMedia), http://ablemedia.com/ctcweb/showcase/wardgladiator1.html, retrieved 2007-01-26

- Winkler, Martin (2004). Gladiator Film and History. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1042-2

External links

- Gladiator at the Internet Movie Database

- Gladiator at Allmovie

- Gladiator at Box Office Mojo

- Gladiator at Rotten Tomatoes

- Gladiator at Metacritic

- David Franzoni (1998-04-04), Gladiator: First Draft Revised, archived from the original on 2008-03-16, http://web.archive.org/web/20080316123637/http://www.hundland.com/scripts/Gladiator_FirstDraft.txt, retrieved 2007-01-01

- David Franzoni and John Logan (1998-10-22), Gladiator: Second Draft Revised, archived from the original on 2008-03-12, http://web.archive.org/web/20080312054408/http://www.hundland.com/scripts/Gladiator_SecondDraft.txt, retrieved 2007-01-01

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by American Beauty |

Academy Award for Best Picture 2000 |

Succeeded by A Beautiful Mind |

| Golden Globe: Best Motion Picture, Drama 2000 |

||

| BAFTA Award for Best Film 2000 |

Succeeded by The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||